Some posts on this site contain affiliate links. If you book or buy something through these links, I earn a small commission (at no extra cost to you). Take a look at my privacy policy for more information.

Wayyyyyyy back in 2014, I spent five months backpacking through South America with my then-boyfriend. After making our way through Colombia and Peru, we crossed into Bolivia at Lake Titicaca – the highest navigable lake in the world!

Throughout the trip, I wrote blog posts and shared them almost in real-time as we went. Those posts are now nearly a decade old, so are probably too out of date to be of any use to other travellers.

They’re also a little embarrassing! I like to think I’ve improved a lot as a writer in the last decade – and these posts are more like nerdy diary-style blog entries written on the fly.

Realistically, these blog posts don’t have a place on my site any more. But that South America trip was a huge chapter in my life – and a turning point in my career as a blogger. These blog posts are part of the journey that brought me to where I am today. So instead of deleting them all, I’ve gathered them all up, in order, onto one page.

Honestly – I’m only keeping these blog posts here for me, because they have so much sentimental value! I’m only writing this intro in case anyone stumbles upon this page and wonders what’s going on!

So without any more self-deprecating rambling, here are my Bolivia diaries in all their pure, naive glory…

- Isla del Sol, Lake Titicaca

- Red Caps Free Walking Tour, La Paz

- Urban Rush La Paz – Running Down a Building in Bolivia

- La Paz Football Match

- Red Caps Extended Tour, La Paz

- Torotoro National Park

- Stopping in Sucre

- Siete Cascadas

- El Canyon Tupiza

- Quebrada de Palmira in Tupiza

- Salar de Uyuni Tour from Tupiza in Bolivia

- Alternative Salar de Uyuni Tour: the 4-Day Tour from Tupiza

- Salar de Uyuni Tour: Day One

- Salar de Uyuni Day Two: Lakes and Mountains

- Salar de Uyuni Tour, Day Three – Rocks and Bones

- Salar de Uyuni Tour, Day Four – Sunrise and Salt Flats

- Uyuni Train Cemetery

Isla del Sol, Lake Titicaca

28th – 29th April 2014

If our experience of the Peruvian side of Lake Titicaca (Puno and the overly touristic floating islands) was something of a disappointment, the Bolivian side more than made up for it.

After a slow border crossing, where everyone on the bus filed first to the Peruvian police station, then to the immigration office for exit stamps, then over the border on foot and into the Bolivian immigration office, we made it into Copacabana. Not a particularly lively or picturesque town, we enjoyed it simply for its relaxed vibe and incredible views. We spent the next morning walking along the edge of the lake over the stubby grass and shingle beach, and eating in one of the two colourful, hippy-ish restaurants that face the port, before hopping on an afternoon boat to the Isla del Sol.

The boat ride took two and half hours, puttering slowly but surely across the lake which, surrounded by green cliffs and disappearing at the horizon with no opposite shore in sight, looked much more like a sea. The sky above, the very air itself, seemed impossibly blue and in spite of the bright, warm sun everything looked cold and weathered.

On the shore, we were accosted immediately by kids trying to get us to stay in one of the three hostels clustered around the tiny beach at the foot of tall, rocky cliffs. Luckily, a local gave us a tip and pointed out that the beach gets no electricity at night and that there are hostels and restaurants in the village at the top of the island, which have better views and face the sunset. So, we headed up the enormous stone staircase, reportedly Inca, past the dubiously named Fountain of Youth (the water feeding into this runs down a gutter beside the steps, so I’m not sure if drinking it would make you younger or just give you a serious tummy problem), and up into the village.

At 4,100m above sea level, the highest we’d been yet, the climb was pretty difficult. But the late afternoon sun was warm, and as we ascended the views behind us across the lake became clearer, until we could see the snowy white peaks of beautiful, silent mountains peeping out from the low cloud bank lining the lake in the distance.

At the very top, we found a relatively cheap hotel – the Templo del Sol, at 30Bs (about £6) a night for private – and then headed out for a short walk to some nearby Inca ruins that were marked, slightly inaccurately, on a map in our hostel. We never reached the ruins, since they turned out to be at the very southern tip of the island down a huge hill with no clear trail or path that we could see, but instead we had a really nice walk in the golden, wintery sunlight, through the small pine forest and around a hilltop covered in wiry bushes and heather-like plants, where a local farmer was watching his sheep.

After our walk, we watched most of the sunset from one of the village restaurants, on plastic tables teetering at the edge of the cliff, as it slid down the sky towards the lake. The island turned slowly golden, the distant sky was a pale, cold pink, and it was set to be one of the most beautiful sunsets we’d watched. But, thinking we had more time, we decided to hike up to the viewpoint at the top of the hill behind the village, and of course arrived just after the sun had completely disappeared behind the distant blue horizon. The electric pink and orange sky it left behind, and the dusty peach coloured light playing on the white mountain range behind us, were spectacular, but it seemed like a huge shame to miss the actual sunset when on the Isla del Sol.

Our night on the island more than made up for it, though. On a recommendation from another traveller, we headed back out of the village to the tiny stone cottage Las Velas on the edge of the pine forest. From the outside, it looked shut, with no lights on, no sign, and no sign of life through the dark windows. We tried the door anyway, though, and found a tiny, cosy little restaurant dimly lit by five or six candles on as many small tables, where a few other couples and groups of travellers were sitting, quietly chatting and playing cards, so that the noise was not above a murmur. Although it sounds a little eerie, the atmosphere was beautifully intimate and I loved it straight away.

Although we had to wait a long time for our food (there’s only one chef, also the owner, and he serves everyone at the same time so that we all eat together), it was worth the wait. Perfectly cooked Filet Mignon in a gorgeous mushroom sauce, with proper mashed potatoes (something hard to find in South America), not to mention the delicious wine; it was easily one of the best meals we’ve had on our trip. The owner was absolutely lovely, too, chatting to everyone and making sure everything was perfect. When we left, our bellies grossly overfull, he showed us to the door and outside, after I remarked on the stars in a gushing awe that was totally genuine, he pointed out all the constellations for us, including the Southern Cross. The night sky was absolutely breathtaking; the milky way – which I’d never seen clearly before – was visible, as well as dozens of crystal clear constellations. I walked home with my neck constantly tilted upwards, barely able to tear myself away from the view, and utterly in love with the Isla del Sol and our first taste of Bolivia.

Day Two

Our second day on the Isla del Sol was even more beautiful than the afternoon before. The sky over Lake Titicaca was a constant vivid, empty blue, and the air at this altitude smelled fresher and cleaner than any I’ve smelled before.

We fuelled up greedily with a huge breakfast, then headed out at about ten to walk the length of the island. Having spent the night in the village of Yumani in the south of the island (where the most hostels and restaurants are to be found) we walked all the way to the north of the island, rounding the tip, to the village of Challapampa to get the afternoon boats from there.

The walk took about three hours, weaving constantly up and downhill through beautiful scenery. Shortly after leaving Yumani, we passed a checkpoint and had to pay tax of 15Bs each to pass into the northern section of the island, allegedly for upkeep of the archaeological sights. Although every uphill was hard, the walk wasn’t too tough and the stunning, 360 degree views of the lake were a spectacular reward.

In the distance ahead, a thin blue line proved the enormity of Titicaca, disappearing over the horizon like an ocean, while to our left the island fell away in small, model-railway hills coated in neat, stubby grass, to bays of startlingly turquoise water with thin, sandy beaches. Behind us to the right, the mountains we had glimpsed the day before still rose above the low cloud bank, which clung to them like children, while the white peaks remained glassy and unmoved.

At the far end of the island, we reached the Inca ruins; roofless, stone houses with gapingly empty windows and doors. The houses hinted at history, but the island itself felt ancient: the silence, the dirt tracks, the few spindly pine trees and the weather-worn mat of grass tangled with spiky bracken. Mildly interesting, the Inca ruins felt limp after Machu Picchu, especially when we saw the squat, stone Inca table, reportedly once used for sacrifices, laden with souvenirs and watched over by a bored old man.

The final part of the walk crossed farmland. Stone cottages on sloping hillsides, pigs tethered by the side of the path, a flurry of colourful flowers shivering in the blueish sunlight. It was a slow, peaceful, beautiful path that curled around the hillside and down to a shingle bay, where white painted rowing boats were moored behind a silent town.

We bought tickets at the tiny harbour and, having arrived only ten minutes before the boat left at 1:30pm, headed back to the mainland shortly after our walk. The Isla del Sol is still one of my biggest highlights of Bolivia, and was the perfect way to enter the country. Looking back, I wish we’d spent longer on that peaceful, beautiful island.

Red Caps Free Walking Tour, La Paz

2nd May 2014

Following our fantastic experiences of the free walking tours in Cusco and Arequipa, we decided to kick off Bolivia with the free Red Caps City Tour of La Paz.

We started in the Plaza San Pedro, where our two guides, Andrea and Mauricio, who were both really friendly and really funny, started out by giving us a ton of information about one of Bolivia’s most infamous tourist attractions, San Pedro Prison.

San Pedro Prison

Anyone who’s read Rusty Young’s Marching Powder will already know all about it, but for those who don’t the prison is a fascinating feature of La Paz with a really strange history.

San Pedro has capacity for just 400 prisoners, and from the outside, you can see how small the building is. But currently there are over 2,500 people inside, including prisoners’ wives and children who live inside with them because they can’t afford to pay rent on two places at once.

That’s right, rent: in order to stay in San Pedro – regardless of the fact that you’re there unwillingly – you have to pay rent, which varies depending on what part of the prison you stay in and how nice the accommodation is. Prices start at around 50Bs a month for a bed in a cramped, ten-bed cell, and go right up to 5000Bs for full apartments complete with en suites, LCD TVs and kitchens.

With so many prisoners and other people living inside San Pedro, the number of guards, just fifteen, seems ridiculous, and that’s on a good day: on public holidays like the Labour Day Weekend, there can be as few as four guards at a time outside the prison!

Since they need to pay rent, and to buy food, cigarettes and everything else inside the prison, prisoners need a way to earn a living. So, tons of businesses have sprung up inside San Pedro; salons, restaurants, coffee shops, spas, electrical goods, repairs. Apparently, the food places get the best income because Coca Cola pay them directly for exclusivity and advertising, and there are three deliveries of Coca Cola a week!

Other prisoners make souvenirs, and their wives head outside the prison every day to sell the handmade goods to unknowing tourists, while others still keep up the business they got into San Pedro for in the first place: drug dealing.

A lot of coke is actually produced inside the prison, and dealers either sell it while they’re on day release, or they have a network of dealers outside the prison to do the job for them (and risk their own cosy spot in San Pedro). Mauricio and Andrea showed us a small hole in the roof of the prison in the left-hand corner, through which the coke producers throw packages wrapped in nappies for someone waiting outside to pick up and deal.

During one of the Red Caps tours, they actually saw a package fly out of the prison roof and land on the pavement, but because so many tourists noticed the police, who usually turn a blind eye, felt compelled to pick it up!

San Pedro prison is famous amongst tourists thanks to Marching Powder. The author actually spent a few months living in the prison with a British prisoner, Thomas McFadden, and the book is all about him. Thomas, arrested for smuggling coke in Bolivia, was living in San Pedro prison and decided to run tours as a way of making money, and San Pedro became infamous amongst backpackers as an unlikely tourism destination.

Nowadays, following numerous assaults and stabbings (there are no guards inside the prison, so it’s pretty dangerous), the government have shut down the operation, and anyone who offers you a tour of the prison is either going to take your money and run, or worse, leave you inside San Pedro with no passport, no money and no way out.

La Paz Market

From prisons and scandal, we headed up the road to a more normal corner of La Paz life; the huge open-air market. In the fruit and veg section, we passed dozens of traditionally dressed, double-plaited cholitas, all seated at stalls laden with vegetables, bananas, apples, exotic fruits, and endless potatoes, including the tiny, pebble-like white potatoes which are dried out following an Inca technique and which, apparently, keep for up to twenty years.

With every stall selling exactly the same selection of goods, it’s hard to know how any make a living, but our guides explained that everyone who shops at the market has their favourite lady, and go to her again and again, so actually, it’s the women with the best gossip, banter or conversation that get the most customers. Once you’ve shown one cholita a bit of loyalty, she will start to give you the “yapa”, a local term meaning “the little bit extra”, and maybe give you a couple more apples for the same price everytime you visit.

Cholitas in La Paz

The guides were also full of a lot of funny facts about cholitas. I mentioned before that these big, plump women, dressed in about twenty skirts at a time and with as many cardigans, are ridiculously strong, hoisting sacks of potatoes as big as me onto their backs and plodding uphill without a problem.

The small bowler hats they wear were apparently a result of a mistake by an Italian company; they set up business shipping hundreds of hats to South America for the indigenous men to wear in imitation of their colonial masters, but unfortunately sent over a boat-load of hats that were way to small, and couldn’t sell them.

Not wanting their investment to go to waste, the company quickly marketed the hats to indigenous women, instead, saying that they were the latest trend amongst European women.

The women apparently loved the hats, and have been wearing them ever since, so that they’ve even become a symbol of relationship status; a hat worn straight-up means the lady is married, while one tilted to the side means the cholita is single or widowed and available for marriage.

Flirting is even more bizarre: according to Mauricio, the sexiest part of a cholita is her calf, which is usually covered up by her many heavy skirts. So, when she wants to flirt, a cholita will pull the skirts up slightly, revealing her “big, juicy, brown calf” (Mauricio’s words), and if the man is interested he’ll then start to chase her, while all the while the cholita pretends to protest.

It all sounds pretty bizarre to Western ears, but actually the cholitas are really well respected amongst Bolivians and to dress as they do is considered a sign of status. Apparently, the best outfits can cost thousands of dollars to put together, so the more money a cholita has the nicer her clothes, and, as a result, the higher her status.

La Paz Witches Market

On the outskirts of the market, we also walked through the small witches market, where stalls were laden with bones, feathers, amulets, and hundreds of furry, skeletal dried lama foetuses, which looked like macabre puppets.

Mauricio – dramatic and very camp – was full of funny facts about the kinds of potions of offer, from a spell to make your lover become your slave, obeying everything you say, to a Viagra-type pill meant for horses which resulted in a lot of men turning up dead on ‘prostitute alley’ up in El Alto.

He particularly enthused about the “follow me, follow me” and “come to me, come to me” dusts, which he hopes to use on newly single Prince Harry, the first of which makes your unsuspecting victim fall obsessively in love with you, and the second of which will essentially get their pants off!

The guides also talked about some of the rituals which still go on today, usually to ask Pachamama (mother earth) for luck, money, or possessions. When a new property is being built, a ritual will be carried out to bury a lama foetus under the foundations, which will ensure the success of the project.

An urban legend, which our guides both sincerely believed in, says that for larger properties, like hotels and apartment buildings, a much larger sacrifice is required. A witch doctor will head out into town after dark and, so the story goes, find some homeless people to get drunk with.

Eventually finding the tramp with the least to lose, with no family to miss them etc, the witch doctor will get the poor victim so drunk that they pass out, and then use them for a much larger, more elaborate ritual in which the homeless person will be sealed into the building’s foundations with concrete, still alive so that Pachamama can kill him herself.

Plaza Murillo

From that disturbing tale, true or not, we headed back out into the light for a look at the San Francisco church, and then into another market, Mercado Lanza. where we tried some delicious fruit smoothies for just 8Bs each (80p) and some rellenadas, fried potato cakes stuffed with meat, veg and hot sauce.

Then it was up to Plaza Murillo for a view of the presidential palace and some history of Bolivian politics, which was pretty fascinating – and violent.

As recently as 1946, President Villarroel, was thrown from the palace balcony and hung from a lamppost by a mob. The guides also had a lot of great stories about the current president, Evo Morales, but we went to the final stop of the tour – on the 17th floor of the El Presidente hotel – to talk about him.

Evo Morales

It seems as though the president has done a lot of good for the country, from the brand new, solar-powered cable cars around La Paz, to securing the country’s economy, to converting the Republic of Bolivia to the Plurinational State of Bolivia, uniting and recognising all the indigenous groups within Bolivia.

However, he’s also frequently put his foot in it during speeches or announcements, with a lot of humorous effects. Reportedly, Evo once announced that eating too much chicken will make you gay, and drinking too much Coca Cola will turn you bald, subsequently having to publicly apologise to chicken farmers, homosexuals, Coca Cola and bald people.

Returning from a trip around the world, the president declared to his press team what he’d learnt: that Bolivia has the highest number of Bolivians living in it. Very insightful.

Attempting to combat the country’s low population, Evo tried to raise the tax on condoms, charge taxes to women over 18 that had not yet had a baby, and give bonuses to women who had. He later withdrew the first two actions, and publicly apologised to women (and, presumably, makers of condoms). I’m pretty sure that he’s made even more comical mistakes over the years, but in general, it seems he’s a good president!

Tour concluded, I stayed where I was on the seventeenth floor of the hotel to experience Urban Rush, which I’ll save for another post!

La Paz Free Walking Tour – Info

Red Caps free walking tours of La Paz leave from Plaza San Pedro (under the statue) at 11am and 2pm every day – look for the Red Caps!

Urban Rush La Paz – Running Down a Building in Bolivia

2nd May 2014

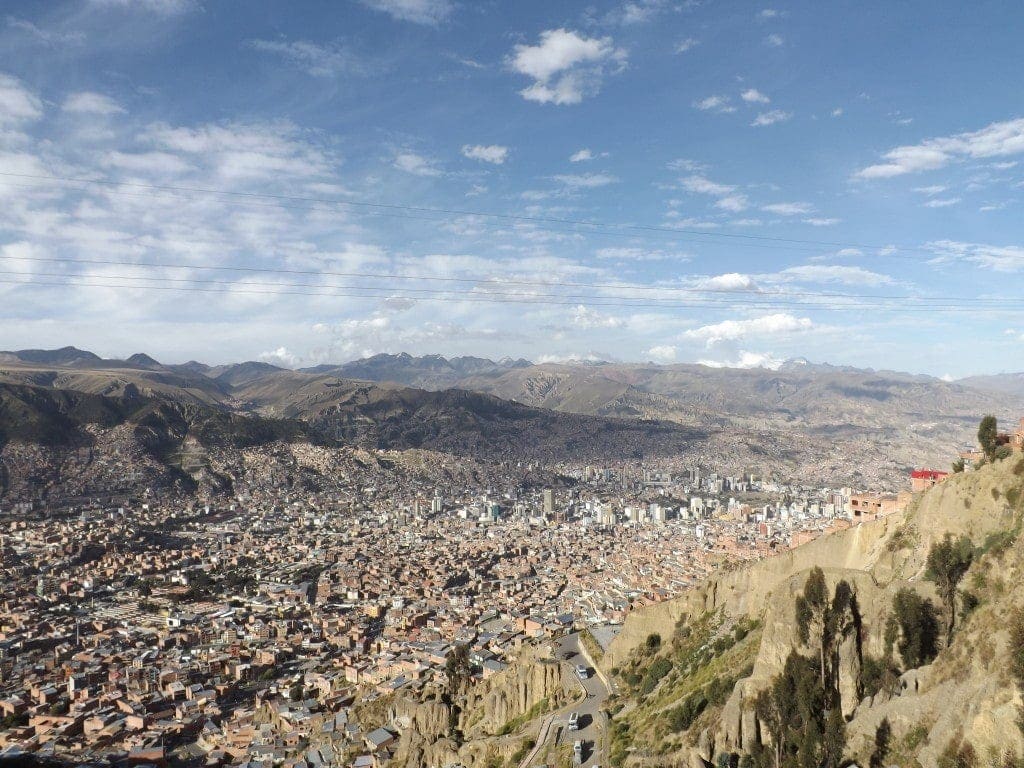

The awesome free Red Caps City Tour of La Paz finished on the seventeenth floor of the El Presidente hotel, which provided amazing views across the city as far as El Alto up on the hill behind, and to the snow-capped mountain overlooking downtown.

This floor of the hotel also happened to hold the office for Urban Rush, for which Red Caps guests get the discounted price of 100Bs (about £10) instead of 150Bs, so straight after the tour I signed up for a jump.

Urban Rush La Paz

Urban Rush are an extreme sports company that basically offer the chance to abseil or rappel down the outside of the hotel, then freefall several stories to the bottom. This is even scarier than it sounds; seventeen stories is a long way and you have to lean out of the window over rushing traffic to get started.

Out of our tour group of about twenty or so people, all backpackers between 20-30, I was the only one to do the jump, even Sam didn’t want to do it (although apparently this is not because he was afraid, he just didn’t feel like it). While I was getting prepped and filling out the usual ‘if I die it’s not your fault’ forms, two other girls showed up to do the jump at the same time as me, so I wasn’t alone.

The whole time we were getting harnessed up and trained, I saw my fear reflected in their grim, greyish faces, but I think, surprisingly, I dealt with mine quite well. The two girls barely said a word to me or to each other, looking like they might be sick if they opened their mouths, but I was chatting and trying to make jokes, to lift the tension.

Getting Ready

Part of the attraction of the jump is that you can do it dressed as your favourite superhero, or as Santa or even a rasher of bacon, depending on your taste! After toying with Mario, I settled on Batman and got suited up in some very flattering black overalls sporting the yellow bat symbol. The harnesses went on top, and then it was time for the training wall, where our instructors showed us how to lean forward to a 90 degree position facing straight down.

We had to feed the rope through our hand little by little to slide ourselves forward, while one guy at the top and one at the bottom held onto to the brakes, ready to catch us. Standing on the edge of a four foot wall above a blue padded crash mat, and simply leaning forwards to face down, is HARD. Almost impossibly hard, and worse was the urge to keep a tight grip on the rope once I was in position and started walking. If you hold the rope, it doesn’t move and you can’t walk forward, so instead your legs slip out in front of you; exactly what happened to me the first time I tried.

Rappelling Down a Building in La Paz

Training over, we headed over to the window itself while the speakers ominously blared ‘Bang bang, my baby shot me down…’. Learning from my zip lining experience that a long wait only makes nerves worse, I volunteered to go first, but not before one of the instructors had run down in about four seconds to show us ‘how it’s done’. I was clipped into the ropes and hopped up onto the window ledge where, heart thumping, I shuffled my toes over the edge until my feet were almost half off.

Leaning forward over that heart-stopping drop is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Looking back, I’m not sure why I wanted to do the jump so badly anyway; I have a huge fear of heights and a generally nervous disposition. I think I just wanted to prove something to myself, or try to conquer the fear which so frequently gets in the way of having fun on my trip. But, suddenly there I was, leaning forward until I was standing horizontally over La Paz, and despite the strong grip of fear it was almost fun.

Bring it On

Then I started walking, and, just like in training, the urge to keep a tight grip on the rope, which felt like the only thing supporting me (despite the two men braking me at either end), was too strong. I held on for just a little bit too long while I kept walking, my feet went further than my body, and I slipped.

The only similar feeling I can think of is The Detonator at Thorpe Park, which hangs you at the top for a few teasing seconds before suddenly plunging downwards as your stomach flips and your head reels. For a horrific moment, I felt nothing but cold, hard fear seizing my body, but then I felt the strong grip of the rope which held me and realised that I wouldn’t fall.

My trainers were so slippery that I couldn’t get enough grip with my feet to stand back up, so after a small scrabble – which Sam, watching from the street below, said was the most horrible thing he’s ever watched – the instructor shouted down to me to jump instead. I took the next few storeys in frog-like leaps down the building, feeling slightly less glamorous than Batman, but actually enjoying myself all the same.

Freefall

About half-way down, the instructors braked the rope so that I couldn’t go any further on my own, and shouted for me to freefall. I let go of the rope, held my arms out in front of me, and jumped off from the wall as hard as I could. At the same time, the two guys let go of the brakes and I fell – plummeted is the word, I think – down several stories in a whirlwind rush which was absolutely amazing. A bigger thrill than any rollercoaster, a brief feeling of almost flying, a huge hit of adrenaline coursing through my body: the feeling was incredible.

One storey from the bottom, my instructors braked me again and the guy at the bottom helped lower me down to solid ground. My whole body was trembling as he helped me out of my harness, and I was so full of excitement, fear and total elation that I almost burst into tears.

The experience was absolutely incredible, terrifying and fun in equal measure. But, as the Mark Twain quote on the Urban Rush poster points out, “courage is not the absence of fear, but the mastery of it”.

La Paz Football Match

30th April 2014

Our first days in new cities usually seem to go more or less the same. We arrived in La Paz late at night and checked into what turned out to be a pretty horrible hostel, so spent the morning of our first day seeking out a better one, then spent the rest of the day eating, resting, and catching up with important details like emails and backing up photos.

But on the evening of our first day, we managed to do something a little different, and went out to watch a football match between local favourites Bolivar and Santa Cruz’s team Blooming. We arrived at the stadium in style, with seven of us squeezed into a five seater taxi, and I rolled out of the boot to discover a whirlwind of traffic, food stalls, souvenir stands, crowds and confusion. This was pretty much my initial impression of La Paz; dirty, messy, busy, crowded and just a little crazy – an atmosphere that maintained for most of our stay there and although overwhelming, it was also pretty fun.

The tickets for the match were so cheap, for just 40Bs (about £4) we had the best seats in the stadium, right on the halfway line. Now, I should admit I’m not a huge fan of football, in fact I pretty much loathe it. I can’t follow the sport, I hate the fans, I lose my boyfriend to BBC Sport text updates and every televised Arsenal match he can get to, I think the players get paid too much money… well, the list goes on and on. But, when the teams are smaller and not absurdly rich superstar primadonnas, and the atmosphere is good, I can get pretty into a live game.

That was what I discovered at the Bolivar vs Blooming match, especially after we all picked the first to score (more or less at random, since none of us knew any player’s names or anything else about the team) and then excitedly cheered our players on.

Not only was my player the first to score, but my prediction for the final result of 6-0 also came true. Partly due to poor Blooming coming from a town 416m above sea level and having to play at an uncomfortable 3,500m, which left them all shakily tired out wrecks within minutes, but also possibly due to Bolivar being the better team, the goals kept coming making the match really exciting.

Not being a football expert, or even much of a fan, I can’t offer you any details on the match other than that it was pretty exciting to watch. The atmosphere amongst the crowd, even though the stadium was nowhere near full, was electric, with the fans at the goal end playing music constantly (a full band with drums, horns etc) and the whole crowd going wild with cheers at every goal. At regular intervals, the chant of Bo-bo-bo li-li-li var-var-var echoed round the stadium, and even tiny two year old boys were leaping out of their dads’ laps to celebrate with an intense passion.

We joined in with the chants where we could, and had a fantastic evening watching the game. Even for someone who doesn’t like football too much, the atmosphere at a South American live game is incredible and makes for a really good night out!

Red Caps Extended Tour, La Paz

5th May 2014

After the awesome free Red Caps Walking Tour of La Paz, we wanted to experience even more of the city with them, so on our last day in the unofficial capital of Bolivia Sam and I headed over to Oliver’s English Tavern, the meeting point for the daily Extended Tour.

Although not free, at 100Bs (about £10) per person for a three hour tour, it’s pretty good value, and we actually had a private tour as no one else turned up that day. The idea of the Extended Tour is to take tourists ‘off the beaten track’, to see a side of La Paz that they would normally miss, and there are some really interesting stops throughout the city, some of which are a little dangerous or hard to find, so the Red Caps tour is a great way to connect tourists with these places in the safety of a local guide.

Our guide, Marcello, was a political science student who runs the tours between classes, so he was full of interesting information about Bolivia, especially politics. The tour uses all local transport – which is so much easier to navigate with a local at your side! – so we hopped on a crowded mini bus to reach our first stop, the cemetery.

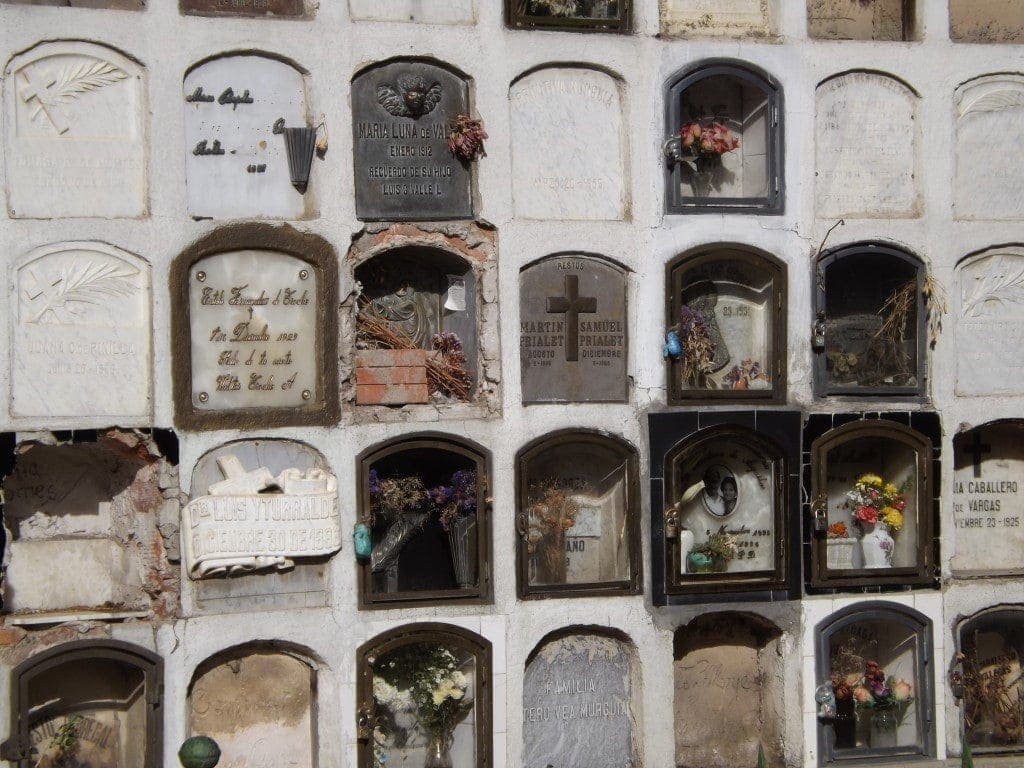

Although not an obvious choice for a tourist destination, cemeteries can be a great way to learn about a different culture and are often the most tranquil or green parts of a city. That was definitely the case with El Cementario in La Paz, a huge, quiet space surrounded by the frenzied chaos of the city outside. As we walked around, Marcello pointed out the graves of old presidents or monuments to soldiers from wars, with loads of fascinating political history along the way. The grave I found most interesting, though, was Carlos Valverde’s.

Carlos hosted a TV show called The True Voice of the People, which gave the indigenous people of Bolivia a voice and which also helped people with problems from the government, society or within the family. The most popular grave in the cemetery, it’s still draped in flowers years after Carlos’s death, and had two visitors while we were there.

Marcello told us he used to bring flowers to the grave every Sunday with his grandmother, because when he was about five he’d gotten lost at the market and Carlos’s TV show had helped Marcello’s family find him. Interestingly, Carlos Valverde had been running for president before he died, and would have won; the country loved him, and the crowds at his funeral went on for blocks.

We saw three funerals while we were in the cemetery, plus a one year anniversary.

Most graves were the Spanish-style blocks of vaults, and after one year the family have a small ceremony to fit the glass and place ornaments, flowers, photographs and other memorabilia inside the grave – we saw everything from toys to coca leaves to bottles of whisky or Coca Cola.

I was really interested to spot graves marked with eviction notices – apparently, the family must pay taxes- or marked with black crosses to indicate an imminent eviction. It was such an interesting experience, and a really good insight into a more personal, less tourstic side of life in La Paz.

Whilst we were at the cemetery, we got a great view of the new, solar-powered cable car line linking El Alto with downtown La Paz, which had just opened the day before and was the first of three new lines being built by the president Evo Morales.

We pressed political science student Marcello for his opinion of the president, and it seems Evo has done a pretty good job – stabilising the economy, recognising the indigenous groups of Bolivia, and setting up these cheap, quiet and super modern new transport systems to link the poorer districts with the rest of La Paz.

From the cemetery, we headed up into El Alto to explore the witches market above the city. After buying a bag of coca leaves from Marcello’s favourite lady at the market, we headed down a strip of small, metal huts outside which spells were being heated in metal pans over small fires.

Out of the back of one of these huts, with an incredible view of La Paz and the distant, dreamy mountains, we chewed the coca leaves with Marcello and a witch doctor alongside his pet llama and a big bunch of dried llama foetuses.

Although I’ve been assured numerous times that they’re good for the altitude, I hadn’t tried chewing coca leaves before, so it was a pretty novel experience to find my cheek and tongue growing numb as I chewed (although I can’t say I liked the flavour).

Inside the hut, it was dim and cluttered with highly un-witch-doctor-y items like a crocheted quilt and stacks of magazines. We sat down on a lumpy sofa to have our luck read in the coca leaves.

The old man, his lined face creased in concentration, spread a handful of leaves across the table, lined a few up in a pattern, then scattered still more over the collection. From this, using only my name and date of birth, he was able to glean a lot of information.

You might be sceptical, but as soon as he told me I was a good person I realised that this guy was obviously speaking the truth. I won’t bore you with my whole future, but essentially I’m going to be ok.

The witch doctor doled out some pretty good advice, too; he said I want everything now and try to do things too fast, so I should slow down and be more patient. Patience also came into play in my relationship advice: apparently, I have a strong character and try to dominate, so I need to be more calm and patient with Sam, too.

Although I’m a bit of a sceptic, having my luck read was a pretty cool experience and something I’d never have tried on my own, so it was a great stop on the Extended Tour. The rest of the witches market was a large-scale version of the one we’d seen down in La Paz: endless arrays of foetuses, coca leaves, teas, and amulets.

We headed deeper into El Alto to explore the sprawling outdoor flea market, with Marcello on guard the whole way and cautioning us to watch our belongings. Travelling though a daunting section of the city like this, with it’s road of prostitutes and high crime rate, was really interesting, I felt like I was getting a peep behind a curtain into a world I’d never normally see, and with Marcello – who claims to be able to spot any thief, and pointed plenty out – looking after us I felt really safe. The flea market, filled with bizarre sights and smells of meat, cow tongue, fish, choleta underwear shops, pirate DVDs, sheep’s belly, even penis soup (apparently delicious and an aphrodisiac), was a surreal, frantic, colourful area that thronged with the kind of ordinary, everyday life that travellers don’t always get to see.

Before heading back to the city centre, we stopped by the awesome Che Guevara statue on the edge of El Alto. Built entirely from scrap metal, the tall statue with his fat cigar and iconic cap, was a really cool site.

Back at Oliver’s English Tavern, we sampled a free Pisco Sour before saying goodbye to Marcello, then stayed on for dinner before our night bus later that evening. The two Red Caps tours in La Paz were definitely the most interesting and fun city tours we’ve had so far, and left us full of weird and fascinating facts! I only wish we’d had time to try the three hour Foodie Tour as well!

Information

The Red Caps Extended Walking Tour meets in Oliver’s English Tavern everyday at 3pm. Find out more at www.RedCapWalkingTours.com.

I paid for my tour in full and all the opinions featured here are unbiased!

Torotoro National Park

7th-8th May 2014

Click here to read about my two days in Torotoro National Park – two days of hiking, exploring caves, and spotting dinosaur footprints!

Stopping in Sucre

9th-18th May 2014

Although we spent ten whole days there – the longest we’ve stayed still on this whole trip – we didn’t actually do a whole lot in Sucre.

We checked in to the lovely Irish-run hostel Celtic Cross, sleepy, peaceful and only two months old, and found ourselves unwinding so quickly after months of travel that we decided to stick around for as long as possible.

The city is beautiful. In the centre, the antique, colonial buildings are all painted a gleaming white, and are lovingly cared for and maintained. The centre of the white city slopes downhill from Churuquella Hill towards the plaza, with rose bushes and flowering trees planted along the streets, while trailing plants and window boxes cling to the buildings, so although there aren’t many green spaces in sight, there’s still a garden-like feel to Sucre.

With not much to do there, you might wonder how we spent ten whole days in Bolivia’s official capital, but staying in Sucre was easy – tearing ourselves away was the hard part!

We spent most of our time – in between some incredibly cheap, and absurdly helpful private Spanish lessons – unwinding in the sun, eating some cheap, good food, and chilling out with friends old and new, but we did manage to make our way to a few of Sucre’s best sights, too.

Parque Bolivar was a big, beautiful green space not far from the central plaza, with towering trees, neatly sculptured lawns and bushes, and a gorgeous fountain surrounded by rose bushes and flower beds.

The real highlight of the park, though, was the ice cream parlour in the top left corner (conveniently just opposite my Spanish school) which was recommended to me by my teacher, David. They only sell two flavours – crema, the classic, and another option which varies day to day, but the crema (cream) ice cream was among the best I’ve ever tasted – sugary sweet, milky, and completely delicious.

We also headed for one other green space, recommended by our hostel owner and interesting, if a little voyeuristic; the cemetery. Like the rest of Sucre, it’s mostly white painted, beautifully kept, neatly laid out and very, very peaceful.

We walked through the quiet shade of the tree-lined paths, looking at the different keepsakes and ornaments placed behind the glass of the individual vaults – just like in La Paz cemetery, Coca Cola, Bolivia’s favourite drink, featured a lot – and studying the new, three storey high plots being built towards the back of the cemetery, looking like small, multi-storey car parks.

Along the way, we also passed several men and women sitting by the edge of the main path praying out loud very rapidly. Their entwined chanting hummed in the air, sounding eerily like a voice speaking in tongues, and followed us through the silent cemetery.

There was the Ethnographic Museum; free, quiet and currently showing a fascinating temporary exhibition of colourful parade masks and costumes from across Bolivia, as well as displays of art and photography upstairs. And, of course, there were the markets: Mercado Negro, which we visited on a sleepy Sunday when it was half-empty, where you can pick up bargain-priced clothes and toys, and the heaving Central Market: constantly busy, stinking of fruit smoothies, hot chorizo sandwiches, spices, raw meat, spilt milk, cheese, and the tang of freshly made chilli sauce.

Other highlights from Sucre include watching the sunset over the city – painting the white buildings milky gold – from the roof terrace at Celtic Cross, crepes from the patisserie on Calle Grau close to the plaza, a fashion show thrown in the main square starring Mr Bolivia (among other Mr South Americas) and all the Miss towns from across Bolivia, watching a football match between Sucre and San Jose at the stadium, the chocolate from Para Ti chocolate shop, and the amazing Heladeria Sucre on the plaza. But, the biggest highlight was the gorgeous Villa Antigua, a beautiful restored colonial mansion where we spent our last two nights relaxing in total luxury and comfort.

Sucre is easily the most beautiful city in Bolivia, and one of my favourites in South America. Warm, sunny weather all day, chilly but clear nights, incredible sunsets, good food, and an atmosphere of total peace – Sucre was the perfect space to stop for ten days and just relax!

Siete Cascadas

13th May 2014

I’ve already mentioned all the things we got up to in the beautiful Bolivian capital of Sucre – in between Spanish lessons, that is – but there is one place I left out of the previous post.

On the Tuesday, we got up early and caught a bus to the very last stop on the outskirts of town, to hike to Las Siete Cascades, a series of seven waterfalls surrounded by rocky cliff walls.

The hike was a pleasant one, in spite of a slightly overcast morning: along a dirt track through a small village, where pigs snuffled at the side of the road and young shepherds led herds of goat or sheep down steep, rocky paths to graze.

We had only vague instructions from a friend who’d done the hike the day before, so finding the way was a little tricky, but luckily there were plenty of people around and everyone I asked smilingly pointed that we were going the right way.

We followed the nearly dry river along, clambering over large rocks and hopping back and forth across the skinny steam, until we reached the first fall. This one is tiny and not particularly impressive, but the second was just around the corner and quite pretty.

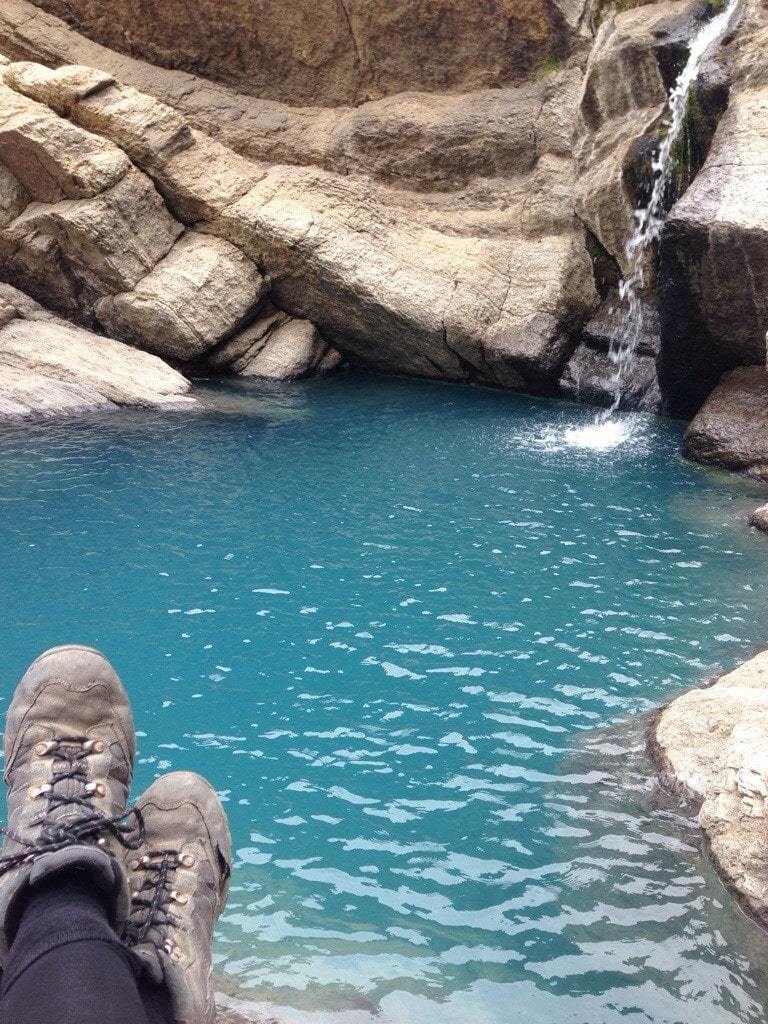

To get up to three and four, there was a bit of climbing involved, first up a steep hill alongside the cliff which waterfall number two tumbled over, then along the top of the cliff and down a rocky channel, where somebody had piled up stones as steps. Waterfall number three was small, but poured into a large, blue pool of icy water, which we had to wade through in order to climb up the mini cliff to get past.

The fourth waterfall was the prettiest we found; at about ten foot high it certainly wasn’t the most impressive waterfall we’ve seen on our trip, but it was surrounded by tall cliffs of smooth, grey rock and it gushed, white and foamy, into a pool of the most unreal blue water I’ve ever seen. The setting was beautiful, although the water in the deep pool was way too cold for swimming (my feet went completely numb after a few seconds), so we sat down in the secluded little rock clearing for lunch. Unfortunately, we couldn’t get to waterfalls five, six or seven. A lot of climbing is involved, and Sam couldn’t get up the cliff-face alongside the fall without a boost – which I was much too weak to give him.

After lunch, we started the hour walk back uphill to the bus stop, needing to get back to town in time for our Spanish lessons. The scenery just outside of Sucre – sweeping green hills and farmland – was spectacular and, with the sun finally shining, the walk was really nice.

Information

Take the Q bus outside the Mercado Central, to the very last stop. You’ll need to ask directions when you arrive, but basically there is a dirt track running parallel to the road where the bus stops (on your right) which you need to follow through the town and downhill to the riverbed. From here follow the river and you’ll reach the falls.

Where sensible shoes: you will need to climb, so no flip flops.

I wouldn’t recommend the walk alone. Some of the climbing bits require a boost or a pull (especially if you’re small and/or weak, like me). A group is best.

El Canyon Tupiza

22nd May 2014

From our old-fashioned mine experience in Potosi, we headed down to Tupiza, a small town set in scenery that looks almost exactly like the Wild West.

After the mine, it was like being in Disney’s Frontierland around the Runaway Mine train! Although, of course, the mine experience was in no way similar to the happy Disney version.

The town is surrounded by walls of blood-red mountains on both sides, with dusty streets and dry riverbeds.

Grey-green cacti stud orange, rocky cliffs, and during the day a hot sun burns down over the dry landscape.

On our first day, we headed for a short walk to El Cañon just outside of town. The walk took us past the military barracks, the cemetery and a small, ramshackle patch of huts belonging to people who make a living panning the rocks for minerals.

Following a shepherd with his herd of goats and sheep, we headed away from civilisation and towards a gaping, craggy opening between the two towering walls of rock.

Inside the canyon, we scrabbled over huge fallen rocks, squeezed into cracks in the sides of the cliff, and generally acted like two overgrown children exploring. The walk was pretty tough going thanks to the boulders filling the dry riverbed, and we couldn’t get very far because we reached a dead end where climbing looked almost impossible.

It was a great place to explore, though, with the rusty orange and vivid red cliffs standing out dramatically against a blue sky, and cartoonishly perfect cacti jutting out from the dry, barren landscape.

Tupiza is genuinely just like the Wild West; its impossible not to be there and think of scenes from any John Wayne movie – or, for geeks like me, hunting scenes from the game Red Dead Redemption – and the colours of the landscape are just incredible, a bizarre contrast to all the green we’d been experiencing in the rest of South America.

Quebrada de Palmira in Tupiza

23rd May 2014

On our second day in Bolivia’s Wild West town, Tupiza, we got up early and headed out to find the Quebrada de Palmira.

Preferring to hike alone, without paying for a tour guide, means that we often get lost; especially as maps and helpful directions are hard to come by in a town that thrives on tourism, where everyone wants you to sign up for one of their tours.

Still, we were determined to go it alone, especially as the hikes around Tupiza, like El Cañon and the Quebrada de Palmira, are really easy and definitely don’t call for a guide.

We headed out of town, following the railway lines along a dirt road lined with stray dogs lazing in the sunshine, where the constant wind threw up swirls of dust into our faces and we had a fantastic view of the distant, rocky mountain wall, the colour of dried blood, which surrounds Tupiza.

Before long, we came across a dried riverbed which had to be the Quebrada de Palmira, and followed it away from the road towards the west.

Although we took a wrong turning at a fork in the river, which led us past a huge, smelly rubbish dump and missed the more pleasant scenic route into the valley, both turns led to the same place, so we arrived at the back of the valley and found ourselves facing an enormous wall of orangey-red rock, blazing in the sunshine, towering above the dried, swirling riverbed and the stumpy, wind-swept green trees which filled the valley.

We headed into the canyon through an enormous gap between the cliffs, and followed the riverbed past (and over) huge pinkish boulders, around enormous clumps of cacti coated in a yellow haze of sharp spikes, and into the Valle de los Machos, also colloquially known as Valle de los Penes (Penis Valley).

So called because of the strikingly phallic shapes of the rocks lining it, Valle de los Penes was formed by water and wind affecting the relatively soft rock of the canyon, creating small, cylindrical towers of rock with slightly larger, bulbous tops. The overall effect is a little bizarre – and according to the locals, decidedly macho.

After a picnic lunch in Macho Valley, we headed back out into the main, sweeping valley and followed a second path round to a different gap in the rock wall, leading into another canyon.

Passing a shepherd with a huge herd of goats, many of whom were stood on their back legs to stretch up and eat the leaves from tree branches, we followed the trail of horse hoof prints (this is a popular area for horseriding tours) to the back of the canyon entrance, where we discovered the Cañon del Inca.

At first glance, we seemed to be in a dead-end; a small clearing between the towering cliffs and huge, fallen boulders. But we saw riderless horses waiting patiently around a watering hole, and decided there had to be a way forward. A lot of climbing was involved!

Up and over the huge boulders, we peeked into the canyon beyond – making jokes about hunting cattle rustlers and attempting Wild West accents – then scrabbled down a narrow, rubble-strewn path, between, over and even under huge slabs of pink and orange rock, into the canyon itself.

The walk was a fantastic one, involving quite a bit of jumping and climbing, and took us through a deserted crevice between two huge rocky cliffs, right into the canyon.

Eventually, we reached a small waterfall trickling weakly over a short cliff, which was really tricky to climb even with Sam hauling me up. I made it though, and we were able to press on for about fifteen minutes more, until we reached a place where an enormous rockfall seemed to have blocked off the rest of the canyon. It looked as though we might have been able to climb it – with difficulty – and carry on, but neither of us wanted to risk a broken neck, or getting stuck on the other side, so we turned back and headed out the way we’d come.

Getting back down the waterfall – where the steep rocks were damp and slippery, and the top of the six foot cliff jutted out further than the lower rocks, making it seem much higher than it was – was even harder than getting up, and Sam had to essentially catch me as I slid down the rockface.

Back outside the Canyon del Inca, we made our way back through the valley along the riverbed, this time following the right path away from the dump. This also took us past one of the other famous sights in the area, the Puerta del Diablo, or Devil’s Gate: a huge, long wall of rock just a few foot wide with nothing on either side, which looks as though it’s been dropped into the centre of the valley.

The gate is a large, craggy gap in the centre of the red wall, strewn with rocks and cacti, and looking for all the world like an entrance to something. We climbed up a sloping dirt path along the wall for an incredible view across the tree-filled valley, its sandy floor laced with the swirls of the river which flows in summer, towards Tupiza and the dark red mountain wall beyond.

Tupiza, with its beautiful, John Wayne film-set scenery and quiet, rustic feel, was yet another of my favourite stops in Bolivia and a great place to spend a couple of days adventuring! It also makes a brilliant starting point for an extended version of the traditional Salar de Uyuni tour – which is exactly what we did!

Salar de Uyuni Tour from Tupiza in Bolivia

24th – 27th May 2014

The Salar de Uyuni tour is easily the most popular tourist destination in Bolivia, and it’s easy to see why. The salt flats themselves are breathtaking, and the three-day tour from Uyuni takes in a ton of incredible sights around that part of the country.

Being so popular, though, can mean that you find yourself following the exact same route as all the other tours, fighting crowds of tourists for a view of each sight.

Alternative Salar de Uyuni Tour: the 4-Day Tour from Tupiza

If you’re looking to escape the crowds, and do something a little different, why not take the four-day tour from Tupiza to Uyuni, instead.

Not only do you get an entire extra day of sightseeing, taking you past things the Uyuni tours don’t get to see, but also doing the route in reverse means that you rarely bump into any other groups, instead you get each spot to yourself and your photos of the landscapes will be unspoilt by crowds.

We went with Valle Hermosa Tours in Tupiza, simply because after getting a few quotes from various companies they seemed like the most organised and experienced, but they weren’t without flaws. I’d say you should get quotes from all the companies in Tupiza, and just see which one feels best to you.

Although the cost of 1295 Bs (about £120) each is pretty high for a backpacker’s budget, this covered food, transport, accommodation and a guide, so it’s a pretty good bargain. The other perk of paying the slightly higher cost is that Valle Hermosa – like most tours in Tupiza – only take groups of four at a time, so there aren’t five or six people squeezed uncomfortably into a jeep.

Salar de Uyuni Tour: Day One

24th May 2014

We set off pretty early at 8:30am, bundled up against the icy morning in two jumpers each, hats and gloves. The first stop was at a mirador above Tupiza which overlooked the strange, red rock formations surrounding the city. The hill we were on was yellow brown, dusted with grey-green scrub grass, but according to our driver the whole landscape is completely green and lush during summer (British winter time) and right now the hill is “muy triste”, very sad.

Back in our jeep, we wound along mountain roads, through a stunning landscape that seemed to change more rapidly then I could write it down. Dramatic red rock valleys gave way to sloping brown mountains, distant green hills became pale grey plains, the clear blue sky turned cold and white. We passed twinkling rivers laced with ice, running water gurgling through the frozen sheets or smashed crystal shards. The landscape was enormous, and mostly uninhabited; with only one other jeep (a second Valle Hermosa group) in sight, it really felt like we were penetrating a huge wilderness.

There was a brief stop on a long, deserted stretch of straight road cutting through the Awana Pampa plain, where llamas plucked despondently at rare tufts of grass, their thick fur buffeting in the sharp winds which bit at us through our winter clothes. It was the first time Sam and I had felt really cold since leaving the UK, so the icy winds were a bit of a shock – and things didn’t improve as we pressed on, heading higher into the mountains. At the next stop, the Pasa del Diablo, we climbed the hill beside the road for a view across the valley – almost blocked out by grey, dust-filled winds – and found ourselves running back to the jeep after just a few seconds, unable to open our eyes – let alone remove the lens-caps from our cameras – because of the dust in the painfully cold air.

From sunny plains of dry yellow grass, the world became deep red earth dashed with yellow, flame-shaped bushes, then gave way again to purple earth, cracked-glass frozen rivers that crunched under the jeep’s wheels, tufts of snow caught on wiry bushes. The trip was a constant journey, brief stops in between a kaleidoscope-changing landscape passing by the window, an endless forward motion. It was the perfect kind of travel. We stopped for lunch in Pueblo San Pablo de Lipez, a miserable patch of tiny grey houses, home to just 112 families, where the ceaseless, ferocious wind flicked endless waves of stinging grit and sand into our faces. We could do nothing but huddle inside the small room where we were eating, and listen to it howl outside, warming up with hot lentil stew and rice.

Climbing ever higher, through swirling clouds of dust as thick as fog, sometimes blocking out the road in front of us, we passed banks of snow clinging to the rust brown rocks of the mountains. At the next stop, none of us could even leave the jeep, peering instead at San Antonio de Lipez through the windows: another tiny, squat, empty town of grey houses and wind.

Surrounded by swirling snow, somewhere high in white-capped mountains that vanished into a thick, blanketing sky, we stood on a mirador above the Pueblo Fantasmo (ghost town) and watched the jeeps drive away down the curling road, praying that they’d stop again at the bottom to pick us up from the town below. Machu Picchu in minature, an abandoned town of stone houses, all roofless, shivered at the foot of a dark, brooding hill under a heavy coat of snow. Underfoot, the white ground was crisp and untouched, and we approached as though we were the first visitors to the town since it’s inhabitants left. In the town, a bizarre place of warring families and something like 17 different churches, we stomped our feet into the deliciously crunching snow, bouncing on the spot to fight the shocking cold of the air.

By the last stop, the whole world had vanished into white and grey. Somewhere in the distance, the faint blue sheet of Lagona Morejon disappeared behind the dust filled wind and icy grey sky, almost completely invisible and obstinately hiding from our cameras. We shrugged it off, disappointed, and headed to another small, grey town lost in bitter wind to find our hostel for the night.

The accomodation was basic, but it was clean, the food was good, and inside my sleeping bag under six blankets, in a hat, gloves and two jumpers, I was warm enough to get a good night’s sleep. We drifted off to the sound of the wind shrieking outside the window, rattling loose doors and windows, and all of us prayed for clear skies the next day.

Salar de Uyuni Day Two: Lakes and Mountains

25th May 2014

The four-day trip from Tupiza to Salar de Uyuni was a constant journey. Most of each day was spent in the jeep, with our guide Andres and awesome cook Dolores, watching the landscape slowly change outside the window, sliding from one scene from the next like a picture book, changing dramatically as we moved forwards.

Our second day of the tour was, unfortunately, full of problems. First there were mixed reports of the weather, with some people saying the roads in Parque Eduardo Alvaroa were impassible, so that our drivers initially refused to take us there. When the weather improved in the morning, they said we could enter the park, but might not be able to see everything – although fortunately the only thing we couldn’t see in the end was the green lake.

After we’d decided to try the national park, it turned out that one of the cars wasn’t working. The drivers set to work on an engine part with some super glue, and we set off almost three hours behind schedule, around 10am. We didn’t mind too much about the delay, until we found out that the driver of the second car had neglected to get up in the night and switch the car on – which they’re supposed to do twice, to stop the engine freezing over – so the delay was his fault, and not an unavoidable accident.

He admitted his mistake and apologised, though, and with the fantastic weather and dazzling scenery we soon got over the delay. We stopped just outside of town to view the Volcan de Uturuncu, a big purple cone in the distance, then stopped again a short distance after as the jeep got stuck crossing a huge, frozen river of ice. Both drivers had to dig the car out while we crossed on foot, snapping the ice with satisfying crackles, and cheering when the jeep finally made it across.

The first proper stop was the Hedionda Lagoon, a frozen, brownish lake of sulphur. Everyone marched out onto the ice to skid around and take photos, but the day’s disasters of course weren’t done, and Sam (it had to be Sam) fell through the ice. It was less falling, more sinking – suddenly, the ice wasn’t under his feet anymore, and he was knee deep in a thick, orange sludge which sucked him back in each time he tried to pull himself out onto the slippery, wet ice sheet.

Once out, his jeans, thermals, boxers, socks and boots were all coated in orange sulphur and all completely stank. It’s a horrible, rotten eggs and body odour smell, and it escaped even the two plastic bags we wrapped all his stuff in, stinking out the jeep. Poor Sam had to strip off in the snow behind the jeep, and change into spare clothes and trainers, but luckily no real damage was done beyond some smelly jeans.

From stinky sulphur, we moved to clean, white soap. The Laguna Kollpa is filled with a natural detergent used by locals as shampoo and soap, and exported to Chile to make cleaning products. The whole lake was white and icy, surrounded by snow, and so bright that it stung my eyes. The white scum floating on top, like frozen foam, felt and smelt just like soap or washing powder, and it was so bizarre to see that naturally floating on a lake between mountains and snow.

We headed next to the hot springs, and just in time: Sam’s dirty clothes were starting to stink out the entire jeep. The pool is a small, shallow pond of super hot water next to a steaming, thermal lake between towering mountains, and was completely surrounded by snow and ice everywhere the hot water wasn’t touching. It was so cold, that the taps in the bathrooms had thick icicles dangling from them, and we were shivering in our swimwear as we hurried into the pool, but the water was dizzylingly hot. The bizarre contrast of bathlike water surrounded by snow made the experience all the more special, and it was easily the best hot spring we’ve been to on this trip.

In the pool, we washed Sam’s clothes and shoes out and hung them on a washing line to dry while we bathed. By the time we had completely relaxed, gotten dressed again, and eaten lunch, we went out to find that all his clothes had frozen solid – the jeans were like a 2D plastic cut-out, and would have snapped if we bent them. Although annoying, it was such a funny sight to see frozen clothes that we couldn’t help laughing!

By the time we reached the next stop, it wasn’t just Sam’s clothes that had frozen. My hair, wet from the hot spring, had frozen into tiny icicles at the ends! Although sunny, it was still freezing cold, and everytime we left the warm jeep we had to bundle up in two jumpers, hats and gloves. We layered up and got out to view one of the most spectacular sights of the day: a huge number of geysers spouting thick clouds of white, smelly smoke into the crisp blue sky. The air gurgled and hissed with the sound of boiling, pressurised water, and the largest geysers, belching out an enormous jet of steam, roared with a sound like an aeroplane engine.

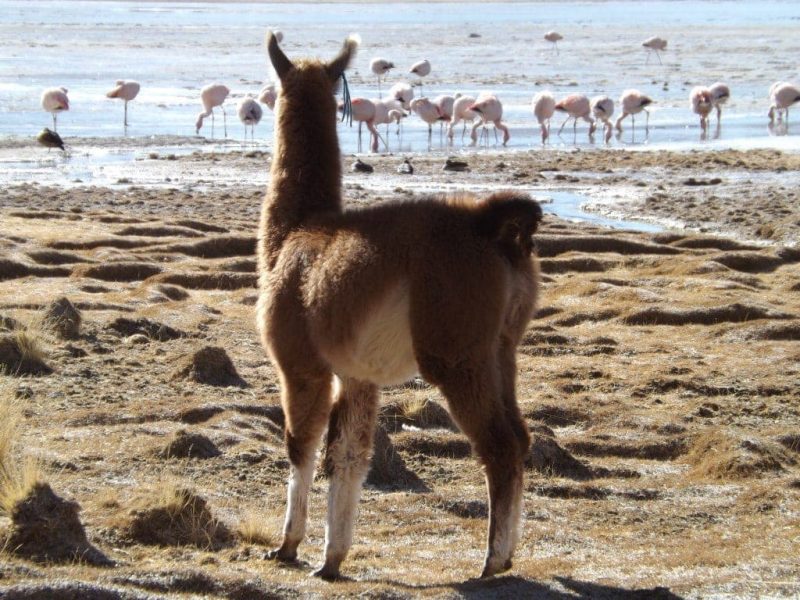

From the geysers, we began to descend. The landscape out the window went from red-brown earth laced with banks of blinding white snow in lines and distant hills dappled dark green and brown between tufts of snow like freckles, to warm, sunny plains of yellow and pale brown grass. We reached the Lagona Colorada, one of the highlights of the park, a lake tinted pale red by minerals, set in a landscape of creamy desert and brown mountains. The lake itself, glimmering in front of a pointed hill and frozen in patches, was a perfect mirror, presenting a crystal clear image of the hills and rocks in reverse, making the most beautiful photos. There was an enormous flock of peachy pink flamingoes, perched on their spindly legs out in the lake, eyeing us suspiciously from a safe distance. At the edge, on a long bank of straw used as a nest, we saw evidence of last night’s ferocious snow storm; hundreds of huge, white eggs, all abandoned and void of life, some cracked and spilling a deep orange gunk onto the white sand. There were also frozen bodies of babies and mother flamingoes that had stayed to protect the eggs. It was a really sad, haunting sight that stayed with me as we drove away.

We stopped soon after in a small town where the hostel was just as basic as the night before, but still clean and pleasant. With no wind and a clear night, we were able to go outside – only briefly, since it was still freezing – to look at the stars: a stunning sweep of billions of twinkling lights, the arm of the Milky Way clearly visible, it was a gorgeous sight to round of a day of dramatic beauty.

Salar de Uyuni Tour, Day Three – Rocks and Bones

26th May 2014

After the fiasco with Sam falling through the ice the day before, we woke up on the third morning of our Salar de Uyuni trip to find his wet hiking boots frozen solid and stained white from the minerals in the hot springs we’d washed them in. As if icicle boots weren’t enough, as we set off into the weak morning sunshine, our jeep got stuck in a frozen river and had to be dug out by the other driver. It looked set to be another day of disasters, but luckily, after the initial ice-related problems, things started to go smoothly.

We rolled and bounced over a dusty dirt road cutting through a sandy plain dotted with thick yellow-green shrubs. The sun on our right was still rising, lukewarm and pale gold, over the plain, backlighting the swirling dust clouds sent up by our jeeps, catching on the blueish mist still settled in the long shadows of distant hills, and wrapping the silent, grazing llamas in furry halos of light.

I thought we’d left the ‘Wild West’ behind in Tupiza, but with the red rocks lining the sandy valley and the stubby cacti dotted across the landscape, we found ourselves right back there. As the jeep lurched through the rocks and the rising sun, I was staggered at how much a landscape could change in just three days; from a hot, rocky valley, to snowy mountains and frozen lakes, to sunshine and grassy plains.

We toured the Valle de las Rocas, stopping at rock formations which have been named after things they supposedly resemble. First up was the Copa del Mundo. Strikingly orange against the now bright blue sky, this lumpy rock shape maybe slightly looked like a world cup – or more precisely, a badly made and slightly wonky cup – but it was huge and the scenery around it, with the blue and yellow smoky plain behind us, was stunning.

The second formation looked a lot more like it was supposed to. Although at first glance I saw a teapot, once we’d parked up at the right angle El Camel really did look like a camel! Hump-backed, with a spout-like appendage jutting out the front like a camel’s neck and head, it stood next to other, perfectly ordinary rocks, as though it had been carved into shape. The boys all immediately climbed up onto its back for photos, but with the first proper foothold way above my head I couldn’t join in.

We also stopped in the Ciudad Italia Perdida, the lost Italian city, where none of us could help climbing up the various formations and cliffs, exploring the intricate, rocky valley. According to our driver, the area is so named because it resembles the winding streets of an Italian town, but I’ve also heard a story that it’s named after an Italian tourist who was left behind there by a tour company once. Who knows?

Laguna Pinta, a beautiful, flat lake with frosted edges and perfect reflections, was full of flamingoes, much closer than they’d been at Laguna Colorada the day before. We were able to get near enough for some great shots, ignoring the tourist from another group who called us ‘amateurs’ for frightening off what was probably the 100th llama she had photographed in Bolivia.

One of the best stops of the day was the Canyon del condor. We approached along a narrow road between high rock walls, where we spotted huge, chinchilla-like viscachas twitching their drooping whiskers, and parked next to a grassy valley swamped by shallow, frozen rivers, a lacy pattern of green-white-blue. It was sunny and hot, and as we walked through the valley, cracking ice sheets and hopping over gurgling streams, we finally pulled off the layers we’d been wearing for the past two days. We walked to the Laguna Negra, a dark grey lake frozen completely solid between pale orange rock walls. A flock of ducks sat puzzled on the icy surface, and the picturesque setting was easily one of the best we’d seen.

We stopped for lunch – a picnic of potato cakes, tuna, rice, and salad served from the back of the jeep – in a sunny, green valley filled with grazing llamas, then pressed on, driving through the small town of San Augustin. On the outskirts were ladies carrying huge bundles of quinoa on their backs, wiry red sticks which are a coloured variety of the usual, wheat-coloured quinoa stalks.

From green valleys and gentle hills, we found ourselves crossing the white desert of Salar de Chiguana, a smaller salt flat not far from Salar de Uyuni. Cutting the ghostly pale landscape in two was the railway track heading for Chile with exported salt and minerals from Parque Eduardo Alvaroa; a beautiful, weirdly empty spot with purple volcanoes in the distance and almost nothing in between.

The last stop was at the cemetery in San Juan, an 800-year-old burial site where we wandered into the deserted, unguarded space without needing to pay the entry fee, because the ticketman was out to lunch. It’s hard to imagine a site like this left completely unguarded and unfenced in any other part of the world, but these bones and relics have been left untouched for centuries, so Bolivians seem to trust in this continuing.

Peeping into the squat, rocky mounds built into the earth as tombs, we came face to face with complete, largely undamaged skeletons, still sitting in the foetal or resting positions they’d been buried in. With almost no information in sight, and the museum closed along with the ticket office (meaning we missed the mummy), we left a little bemused by the cemetery; who was this tribe, and why were their skeletons still sitting patiently in their tombs, grinning up at curious tourists through holes in the dried earth? It was a pretty strange experience, but a very cool way to end the tour.

We spent the last night in the best accommodation of the trip; a hotel build almost entirely from salt. The exposed, white-brick walls were salt (I tasted to check!), the tables and chairs were salt, even our bed (not the mattress) was made from salt. The floor was a crunchy carpet of gravel-like salt chips. Only the bathroom, where I had my first hot shower in days, wasn’t salty! When we spilt a little hot coffee on one of the chairs, the salt actually started to melt and crumble away. Surrounded by salt, we had definitely arrived at the edge of the Salar de Uyuni.

Salar de Uyuni Tour, Day Four – Sunrise and Salt Flats

27th May 2014

It was five in the morning and we were racing through empty darkness, cutting across a blank desert of unlit white, the headlamps of our jeep flitting on tyre tracks in the dust which were the only road we had to follow. Overhead was a bowl of stars, still dazzling even as the sky just above the horizon grew lighter: sharp, electric blue edging against the blackness.

The final day of our Salar de Uyuni tour was the highlight, the crowning glory of four days of touring stunning natural locations across south Bolivia. And it started with a serious bang – a hauntingly beautiful sunrise over the other-worldly landscape of the salt flats. As we sped towards Isla Inca Wari – a dark lump scarring the blank landscape with cacti silhouetted against the brightening blue sky – we saw the moon on our right hanging low above the horizon. Huge and round, it glowed flat and grey behind a thin lace of cloud, with it’s bottom lit into a firey, glowing Cheshire cat grin by the reflection of the approaching sunrise.

We climbed the rocky path to the top of Inca Wasi in darkness, past towering cacti sometimes twice my height. It was freezing cold, and each pant drew in gulps of icy air that hurt my chest and throat. We reached the top to find ouselves facing an enormous, empty sky that was glowing bright orangey-yellow and getting lighter all the time. The scene was like a film set, surreal, a huge sheet of light behind an empty desert landscape. We watched the sun rise between the huge cacti, silhouettes fuzzy with a haze of spines, but it was more a slow brightening of the sky than a sunrise, the sun itself took a long time to appear. Finally it burst over the horizon behind small, jagged hills in silhouette, illuminating the flat, white, salt desert surrounding us in pink and colouring the far mountains pale lilac.

With the sun up, the world seemed real again; the cacti were solid, coloured objects, the path underfoot was no longer a shadowy trail of hidden rocks, the desert was an expanse of white instead of blank darkness. We headed back down the hill to ordinary jeeps parked on gritty white salt that crunched like snow underfoot, and ate breakfast in the icy air with hot coffee and cake to warm us.

Driving through the salt flats was a bizarre experience, with nothing but flat, white, crusty earth in all directions. All the bad weather recently had blown in dust and earth, coating one side of each salt polygon so that looking in one direction we saw a desert of brown, while the other way it was bright white, creating a pretty weird effect. In the rainy season, the salt flats are smooth and wet and perfectly reflect the sky, but in winter when Bolivia is pretty dry, the salt flats dry up and instead the ground is a pattern of cracked white polygons, slotted together like crazy paving.

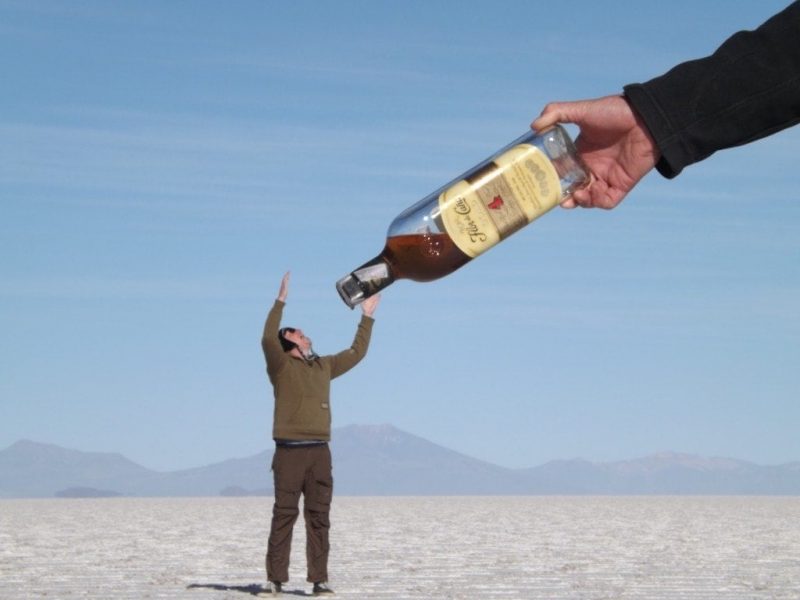

We stopped out in the middle of all this white nothingness for an hour or so, to take the “fotos locos” which play with the lack of perspective on the salt flats. This is much harder than it looks: lying on the ground holding the camera at precisely the right angle, with one figure minuscule in the distance, getting the focus right so that both the foreground and the background seem to be one plain… it’s very tricky! By now, the sun was fully up and the sky was bright blue, with the white of the earth dazzling our eyes.

Somewhere out in the centre of all that white and blue, we pulled up at a former salt hotel which is now supposedly a museum, although it looked a little more like a building site. The exposed salt bricks, missing walls and the sounds of repair work going on inside made it seem very much a work in progress. Apparently, the hotel used to be on the edge of the flats, but the salt grows every year and now the hotel is lost in the middle. You can only enter the museum if you buy something in the shop, but as we all paid 5Bs to use the bathroom we were allowed in anyway. The ‘museum’ turned out to be one very small room housing about six sculptures carved from salt. More picturesque were the world flags collected outside the hotel; strikingly colourful against the blank landscape and brilliant blue sky, they made for some really good, classic photos of the Salar.

Last stop before lunch was to view to small mounds of salt ready for exportation; conical white mounds clustered together on the flats to dry out. Most of the salt harvested at Uyuni is used internally, but some is exported to Chile by train. Nearby is a small town on the salt flat, home to a tourist market and houses for the salt workers, where we stopped for lunch. Our wonderful chef, Dolores – who travelled in the jeep with us and spent the entire four days dozing in the front seat – played a pretty big joke on us when she had us all convinced that we were eating flamingo, but fortunately the tasty wings turned out to be from decidedly not-endangered chickens.

After lunch, we headed out of the salt flats and into Uyuni, where the tour finished outside the bus station. Instead of taking us to the Train Cemetery, the drivers just left us with our bags and gave us directions to the last stop of the tour, which was a disappointing end to an experience which had been, on the whole, good. But, we headed to the Train Cemetery alone (pictures in the next post), and the four-day tour from Tupiza to Salar de Uyuni was a truly fantastic trip.

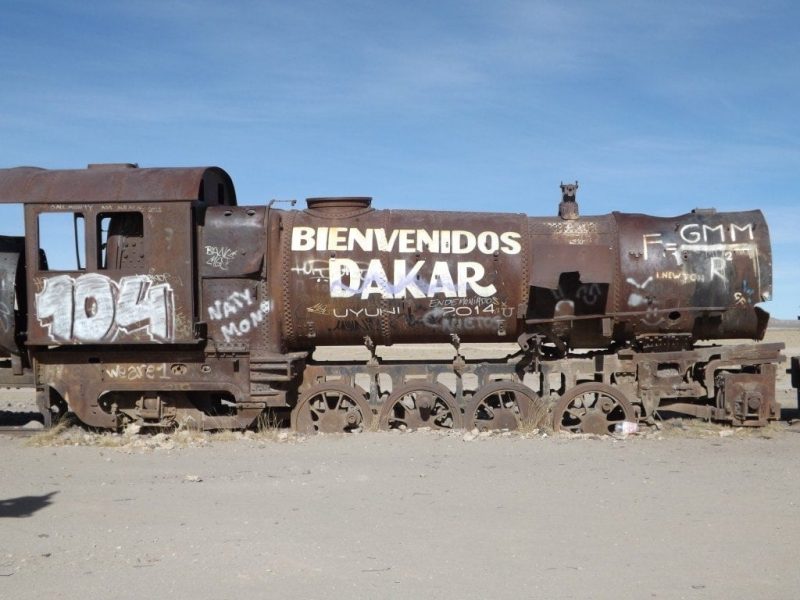

Uyuni Train Cemetery

27th May 2014

Our four day trip from Tupiza to Salar de Uyuni ended in the centre of Uyuni at about 1pm, so from there we headed straight to Uyuni’s second-biggest attraction, the Train Cemetery.

About 3km outside the town, surrounded by a dusty wasteland filled with loose rubbish and stray dogs, this once-busy train yard was a pretty bizarre sight.

Uyuni once served as a distribution hub for trains headed to various ports, loaded up with minerals from Bolivia’s mines, lakes and salt flats, but when the mining industry collapsed due to mineral depletion in the 1940s, the trains were abandoned.

Now, the so-called train cemetery is a huge space filled with forgotten tracks, rusted train engines, and half-destroyed carriages. Lots of the metal is warped or crushed, creating strange, abstract shapes, and many carriages are missing walls and roofs, standing like skeletons in the desert.

The red rust, peeling paint, sun-scorched wood and chipped metal provide textures that are surprisingly beautiful and make fantastic photographs, while the trains themselves, half-destroyed antiques coated in graffiti and surrounded by sandy wasteland, make haunting subjects.

The cemetery was a great space to explore, something like a cross between an art installation, a rubbish dump and a play park; it’s impossible to resist the urge to climb up on top of the trains, or into the cabins, and a few swings have even been added to some of the train wagons.

Although it seems a shame to have so many beautiful, antique steam trains abandoned in the middle of the desert and left to rust, in many ways it’s better than breaking them down for scrap metal, and this way the trains have continued life as a fascinating and strange tourist spot.

Read More

Read more about my South American Adventure in this timeline post.